Psychedelic Frontiers Series – Part 1 | Rebellion to Remedy: The Changing Public Face of Psychedelic Medicine

This insight is Part 1 of the series, “Psychedelic Frontiers: Diverse Perspectives on a Mental Health Revolution“, brought to you by our Healthcare & Life Sciences Strategic Communications team. Our experts embark on a journey to explore the various ways in which psychedelic medicine is perceived across different stakeholder groups, including the research community, medical and mental health providers, and political entities. The first installment of the series will explore public perception of these substances, outlining the how stigma and misinformation have hindered their therapeutic success. The series aims to underscore the nuances of communicating psychedelic medicines with vested parties in order to highlight the therapeutic potential of these substances amid the growing mental health crisis.

In recent years, the conversation surrounding psychedelic therapies has experienced a revival. Psychedelics refer to the suite of substances that affect the brain’s serotonin receptors, leading to altered perceptions, mood, and cognition. Once relegated to the outskirts of scientific conversation, a resurgence of research interest has resulted in substances such as MDMA, LSD, and psilocybin being reconsidered for their potential to treat various mental health conditions, including addiction, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[1]

Despite the growing body of empirical evidence supporting their efficacy, public perception and portrayal of these therapies remain complex and multifaceted, creating confusion and concern that stands in the way of widespread acceptance and integration of psychedelics into clinical practice.

The transition of psychedelic therapies from recreational drug to legitimate medicine is symbolic of a larger societal shift – one that challenges conventional wisdom and invites us to reevaluate our conceptions of what constitutes medical care. Given the historical baggage and perceptions surrounding psychedelic medicines, understanding the evolution from stigmatized substances to medical treatment is critical for success in the next Prozac revolution.

A Checkered Past

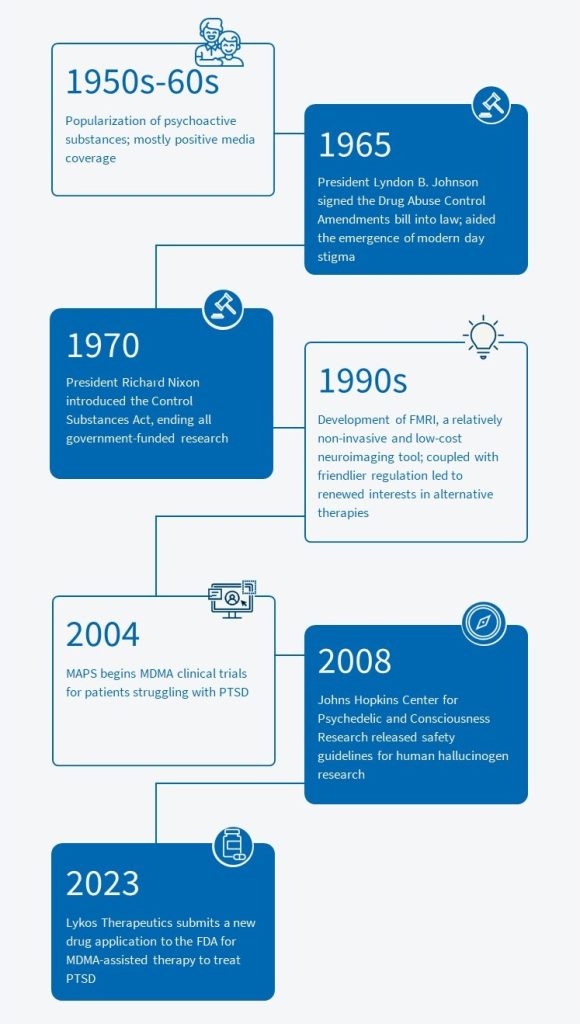

The 1950s and 1960s popularized psychoactive substances as recreational drugs and a vehicle to social change and artistic creativity.[2] The idea of an “expanded consciousness” was promoted through the widespread use and study of Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD.[3] Media portrayal of the drug was largely positive toward the end of the 50s and the early 60s, with coverage largely focusing on the drug’s therapeutic benefits and mainstream appeal.[4]

While some researchers were excited about the potential use of LSD to treat addiction and other mental health conditions, others raised concerns over the loose regulatory landscape and limited oversight governing LSD.[5] These concerns eventually reached the federal government, with President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Drug Abuse Control Amendments bill into law in 1965.[6] This statute prohibited the production, sale, and use of LSD and other abusable substances in the United States.[7] In spite of protests from the scientific community, the law ultimately laid a substantial foundation that played an integral role in the emergence of modern day stigmas and concerns surrounding psychedelic therapies.[8] As a result, media sentiment shifted as coverage highlighted youth substance abuse, LSD as a gateway drug, and anecdotal evidence of people causing harm while under the influence of psychedelics.[9,10] As such, broad societal perception was completely transformed by the villainization of these promising therapies in popular media.

The Controlled Substances Act, introduced by President Nixon in 1970, put an end to all government-funded research into psychoactive substances, including psilocybin, mescaline, LSD, and DMT. However, the development of enhanced research methods and regulations surrounding controlled substances, coupled with an advancement in brain imaging technology led to a renewed interest in alternative therapies.[11] FMRI, a relatively non-invasive and low-cost neuroimaging tool, was developed in the 1990s and enables the use of neuroimaging as a factor in psychedelic research, using scans before and after psilocybin treatment to study its effects.[12] In 2008, Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research released safety guidelines for human hallucinogen research.[13] These guidelines, alongside evolving best practices[14] have set the stage for more rigorous and ethical studies.

The Paradigm Shift

A growing body of research has challenged the negative perception of psychedelics. Studies conducted at institutions such as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), UC Davis, and Johns Hopkins have demonstrated promising results in using psychedelics to treat conditions like depression, PTSD, addiction, and anxiety disorders. This new understanding of the potential of psychedelics as a powerful therapy has shifted researcher and provider perceptions from one of stigmatization to acceptance.

In addition, media coverage has shifted in recent years, contributing to a broader interest in the medical properties of psychedelic substances. Documentaries like “Fantastic Fungi” and “Have a Good Trip: Adventures in Psychedelics” have brought these therapies back into the mainstream, fostering greater understanding and acceptance.

Popular and trusted media outlets have also picked up on these developments, and have broadly been apprehensive of advancements in the psychedelics field as a result of societal and regulatory barriers. A New York Times headline[15] called psychedelic therapies “the next big addiction treatment,” and The Washington Post covered opinion polls, reporting that “it seems clear that it is not just the laws and science around psychedelics that are changing, but also the culture: Americans are moving away from stigmatizing the drugs and toward recognizing that they potentially have real benefits for the treatment of addiction, depression and PTSD.”[16]

Takeaways

While the tide is turning in favor of psychedelic therapies, challenges remain in fully integrating them into mainstream healthcare. Regulatory hurdles, cultural biases, and misinformation continue to impede progress in this field, in spite of recent developments. Recognizing cultural differences – along the lines of history, religion, and social norms – in perceptions and attitudes toward psychedelics will be essential in fostering understanding and acceptance. Culturally sensitive solutions should engage with communities in ways that respects their beliefs and traditions.

Accessible and educational messaging that breaks down misconceptions is paramount in addressing challenges surrounding the acceptance of psychedelic substances as medicine. Information presented should resonate with diverse values, keeping in mind that any approach to psychedelic therapy should be grounded in scientific evidence and adhere to established clinical guidelines to guarantee both safety and effectiveness in treatment.

Traditional and social media platforms will play a crucial role in shaping public perception of psychedelic medicine. By leveraging these channels, advocates and researchers can disseminate medically accurate information that targets the broader mental health community. Expert testimonies and patient stories shared through media can humanize the issue while maintaining strong messaging around their medicinal value rather than the allure of recreational use.

Looking Ahead

As the field of psychedelic research continues to evolve dynamically, so will the public’s perception of these alternative therapies. In the next installment of the series, we will address the complex ethical considerations and regulatory challenges that researchers are facing in conducting research in the psychedelic space.

[1] Kenneth W. Tupper, Evan Wood, Richard Yensen, and Matthew W. Johnson, “Psychedelic medicine: a re-emerging therapeutic paradigm”, Canadian Medical Association Journal (October 6, 2015), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4592297/#:~:text=In%20clinical%20research%20settings%20around,posttraumatic%20stress%20disorder%20(PTSD)

[2] Fred Frommer, “1960s counterculture”, Encyclopedia Britannica (May 8, 2024), https://www.britannica.com/topic/1960s-counterculture

[3] Robert F. Ulrich , Bernard M. Patten, “The Rise, Decline, and Fall of LSD”, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine – Johns Hopkins University Press (Summer 1991), https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/402612/summary

[4] Abigail M Stanger, “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD in American Society”, University of Louisville: The Cardinal Edge, Volume 1: Issue 2 (2021), https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=tce

[5] Abigail M Stanger, “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD in American Society”, University of Louisville: The Cardinal Edge, Volume 1: Issue 2 (2021), https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=tce

[6] “public law 89-74”, U.S. Congress legislation, Congressional Record debates, Library of Congress (July 15, 1965), https://www.congress.gov/89/statute/STATUTE-79/STATUTE-79-Pg226.pdf

[7] Abigail M Stanger, “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD in American Society”, University of Louisville: The Cardinal Edge, Volume 1: Issue 2 (2021), https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=tce

[8] Abigail M Stanger, “Moral Panic” in the Sixties: The Rise and Rapid Declination of LSD in American Society”, University of Louisville: The Cardinal Edge, Volume 1: Issue 2 (2021), https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=tce

[9] Sean J. Belouin, Jack E. Henningfield, “Psychedelics: Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do”, Elsevier: Neuropharmacology, (February 21, 2018), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0028390818300753

[10] Stephen Siff, “Acid Hype: American News Media and the Psychedelic Experience”, University of Illinois Press (2015), https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt14jxvrz

[11] Nicole Ortiz, Charles Preuss, “Controlled Substances Act”, StatPerals Publishing (February 9, 2024), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574544/

[12] Matthew B. Wall, Rebecca Harding, Rayyan Zafar, Eugenii A. Rabiner, et al., “Neuroimaging in psychedelic drug development: past, present, and future”, Molecular Psychiatry (September 27, 2023), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-023-02271-0#:~:text=Neuroimaging%20in%20clinical%20trials,the%20main%20clinical%20trial%20outcomes

[13] MW Johnson, WA Richards, RR Griffiths, “Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety”, British Association for Psychopharmacology, Journal of Psychopharmacology (2008), https://files.csp.org/Psilocybin/HopkinsHallucinogenSafety2008.pdf

[14] Rotem Petranker, Thomas Anderson, and Norman Farb, “Psychedelic Research and the Need for Transparency: Polishing Alice’s Looking Glass”, Frontiers in Psychology, U.S. National Library of Medicine (July 10, 2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7367180/#:~:text=We%20propose%20that%20pre%2Dregistration,and%20particularly%20for%20psychedelics%20research

[15] Brendan Borrell, “The Next Big Addiction Treatment”, The New York Times (March 31, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/31/well/mind/psilocybin-mushrooms-addiction-therapy.html

[16] Benjamin Breen, “Shifting views about psychedelic drugs require a new category for them”, The Washington Post (June 29, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2023/06/29/psychedelics-drugs/

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

©2024 FTI Consulting, Inc. All rights reserved. www.fticonsulting.com