At a Tipping Point – Chilean Private Healthcare Insurers Owe Chileans USD1.4 Billion

Executive Summary

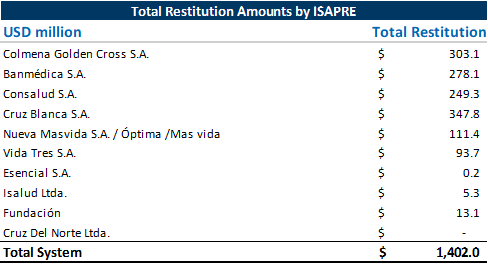

A moment of truth is confronting Chile’s private healthcare system, which is comprised of several foreign-sponsored private health insurers dubbed the Social Security Health Institutions (the Instituciones de Salud Previsional or “ISAPREs”)[1]. The ISAPREs, which have been under protracted financial distress and legal scrutiny, were dealt another blow in November 2022, when the Chilean Supreme Court ruled that these insurers were required to retroactively repay to insured beneficiaries approximately USD1.4 billion in premiums deemed to be “excessive”. In this paper, we examine this tipping point, discussing certain challenges the ISAPREs are likely to face, as well as likely opportunities available to them, including in the spheres of public affairs, business transformation and restructuring, stakeholder engagement and dispute resolution.

The Chilean Health Regime

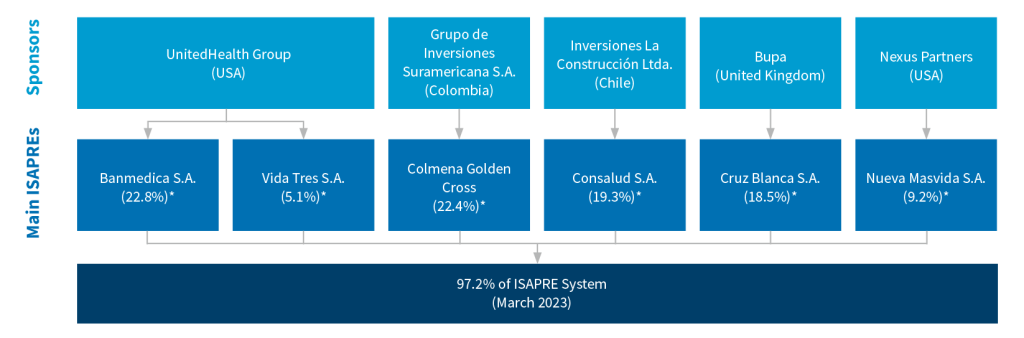

The Chilean healthcare system is comprised of both public and private health regimes. Public healthcare is overseen by the Fondo Nacional de Salud (“FONASA”), the financial entity tasked with the collection, management and distribution of state funds for healthcare in Chile, while private healthcare is overseen by ISAPREs, comprised of several insurers[2].

Chileans must, by law, contribute 7% of their earnings to fund the country’s healthcare needs. [3] In the 1980s, Chilean law was reformed to explicitly allow Chileans the right to choose to direct their contributions to either the state or private system.[4] While this provides the semblance of freedom of choice for Chileans, in reality, the availability of access to private healthcare is limited to those who can afford to pay the insurance premiums, as subsidies for premiums are only available in the public sector.[5] This effectively creates a two-tier system – one for the wealthy and one for everyone else. FONASA is primarily funded by fiscal contributions, with residual funding coming from mandatory contributions of the beneficiaries (i.e., 7% of earnings). ISAPREs, on the other hand, are solely funded by the contributions of the beneficiaries (i.e., the mandatory contributions and additional premiums)[6].

About the ISAPREs

In 2017, there were 14 ISAPREs with 3.4 million beneficiaries.[7] As of March 2023, after years of consolidation implemented to standardize the administration and plans[8], there are now 10 ISAPREs with the top three representing over 60% of the three million beneficiaries in the private system (or 16% of the population) [9]. The decline in beneficiaries over the last few years is likely due to the lack of affordability of premiums in the private system.

Financial Performance of ISAPREs

Over the last several years, the profits of ISAPREs have declined due to increasing healthcare costs (affected by inflation and COVID-19) and expenses related to an increasing number of lawsuits brought against ISAPREs to disallow escalation of insurance premiums.[10]

This issue has been putting pressure on the private system for many years. As noted by the ISAPREs Trade Union Association in 2016:[11]

…there is an urgent and pressing problem; i.e., the litigation of the price adjustment of the health plans. There is full technical consensus that such price increases are not arbitrary; instead, they are called for in order to cover the greater costs of an increasingly intensive medicine that looks after a demanding and aging population, all of which, inevitably, generate costs over and above the rate of inflation and economic growth. This problem – currently impacting the system’s financial stability - requires an urgent solution and cannot continue to be ignored by the authorities because while we attempt to correct the insurance scheme (model), the increasing wave of lawsuits may jeopardize the viability of any given ISAPRE.”

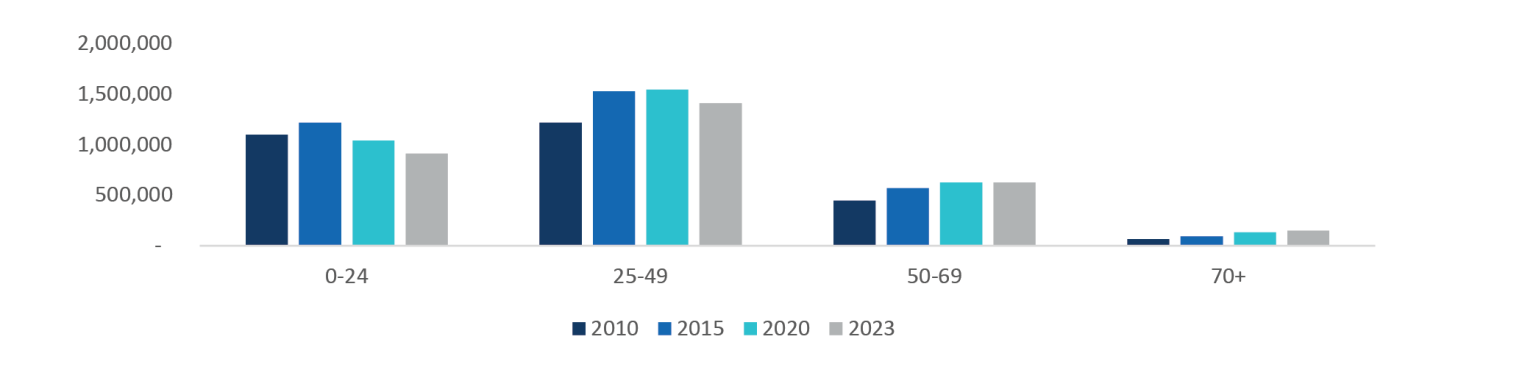

Based on the following data, currently, most of the ISAPREs’ beneficiaries are under the age of 50. However, between 2010 and 2023, beneficiaries over 50 increased by 51%, which inherently increases the costs for the insurers.

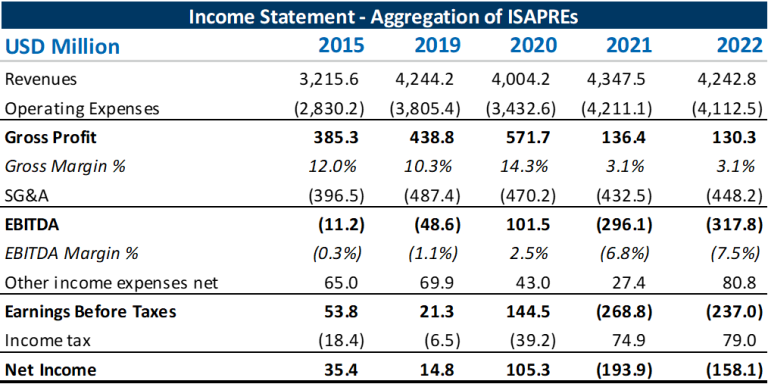

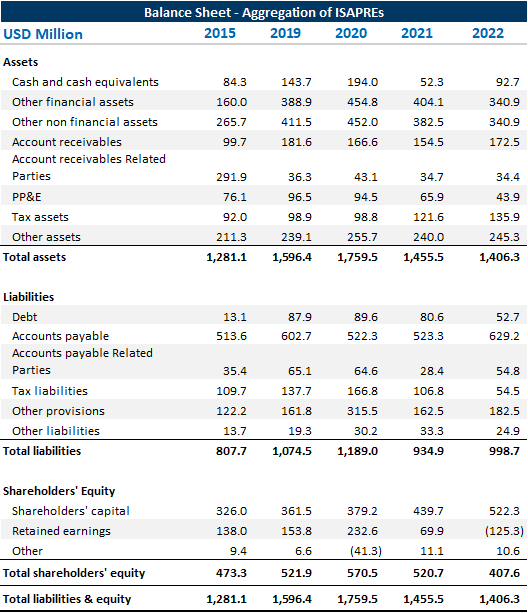

We note the following based on the table below which presents the aggregated income statements of the 10 ISAPREs operating through 2022:

- ISAPREs collectively sustained losses of USD158.1 million in 2022, as compared to 2015 when they generated profits of USD35.4 million. For 1Q23, it was announced that ISAPREs collectively lost USD26.9 million.[13]

- In 2020, the gross margin increased by 400 basis points compared to 2019, mainly due to a 10% decrease in direct healthcare costs for beneficiaries as a result of the postponement of medical treatment during 2020’s pandemic-related restrictions.

- In 2021 and 2022, the increasing gross margin trend completely reversed as, among other cost factors, COVID restrictions began to ease, with direct costs increasing 20% in each of 2021 and 2022 (reducing gross margin by 10% alone). Furthermore, ISAPREs saw an increase in medical leave costs (i.e., payments to a beneficiary while the insured is on medical leave) in 2021 and 2022, likely due to physical and mental health issues from the pandemic.

The Tipping Point: Recent Court Ruling

Against this already strained financial backdrop and years of unfavorable rulings from the Chilean Supreme Court on unconstitutional designations impacting health premiums[15], in November 2022, Chile’s highest court’s ruling has the potential to topple Chile’s private healthcare system once and for all.[16] Specifically, Chile’s Supreme Court ruled that private insurers would be required to apply, retroactively from 2019, a single table of risk factors as calculated by the state to set insurance premiums, thereby preventing these companies from adjusting premiums for a person’s gender, age or other individual-specific risk factors.[17] As a result, ISAPREs are not only facing liquidity pressures given their revenues are effectively being capped, but are also encumbered by the requirement to repay excess fees back to 2019. The total of these fees is estimated to be USD1.4 billion. In May 2023, the Superintendencia de Salud de Chile (Health Superintendence of Chile) published the total restitution owed by ISAPRE as detailed below.[18]

ISAPREs and their sponsors are at a critical crossroads and must evaluate several important questions, including:

- What will be the impact of this regulatory change, not only on ISAPREs but on Chile’s entire healthcare system, the public arm of which is already severely strained with millions of Chileans on waiting lists? Can this information be used to educate and inform stakeholders in an effort to persuade the government and/court to reverse the current path?

- In addition, can ISAPREs adapt by transforming and/or restructuring their businesses in Chile to make the single-premium business model imposed by the Chilean government sustainable in the future?

- In parallel, what are the consequences of challenging the decision and pursuing arbitration against the Chilean government?

Educate and Inform: Advocating for Regulatory Change

According to a recent CADEM public polling, Chileans are calling for health reform and changes, with a majority believing that an ISAPRE bankruptcy would have a large impact in the country[19]. However, reverting the regulatory course can be complex, and only attainable with the right information, communications channels and amplification tools. To defend their freedom to operate in Chile, international insurers need to deploy a targeted multistakeholder advocacy effort that considers the following factors:

Encouragingly, precedent suggests that pre-emptive education and appeals to governments can help in situations where a private investment is expected to be infringed upon but has not yet been damaged.

In 2015, for instance, the Polish Parliament adopted draft legislation relating to consumer mortgage loans denominated in foreign currency, which would have required those loans to be converted to Polish currency, with private banks absorbing 90% of the resultant losses. In response, several foreign banks with controlling interests in the major Polish banks advised of the potential filing of bilateral investment treaty (“BIT”) claims if the new law was adopted. Although likely not entirely because of this petition by private investors, the Senate sent the draft law back to the lower chamber of the parliament for further consideration, signaling a willingness to consider the interests of foreign investors as part of wider regulatory changes.[20]

Adapt: Business Transformation/Restructuring

Private healthcare insurers in Chile have long been under siege, facing public backlash over their steadily increasing premiums to combat rising costs and an aging population.[21] In 2011 and 2012, beneficiaries filed 25,000 and 40,000 lawsuits, respectively, over price increases.[22] In 2019, record levels of lawsuits were filed, reaching 198,000, or 9.8% of contracts, to prevent rises in plan premiums.[23]

As of December 2022, ISAPREs had USD998.7 million in liabilities, of which USD629.2 million were owed to healthcare facilities (including clinics, medical centers, laboratories and doctors), a 20.5% increase from 2020. While ISAPREs have drawn the most attention, the impact throughout the sector is inevitable, with the risk of insolvency high for not only ISAPREs but for all providers that rely on funding from ISAPREs.

The newly imposed regulatory change to require back payment of USD1.4 billion may lead ISAPREs to consider restructuring their businesses, either in or out of court, as it is clear that their balance sheets cannot support the repayment. The cumulative net cash flows of ISAPREs from 2019 to 2022 totaled negative USD16.7 million, with cumulative unlevered free cash flows totaling negative USD25.7 million.

ISAPREs are likely evaluating how to restructure their operations to accommodate the new reality of single price premium and how the business model looks in the long run. They must balance this in the context of the high-level lawsuits filed against them for raising premiums, the inherent structural issues of providing healthcare and the regulatory framework in which they operate. As per MC2 Salud’s article, “Analysis of the Chilean Healthcare (ISAPRE) Sector in 2019”:

By law, ISAPREs must make lifelong commitments to their members, i.e., once accepted, an ISAPRE may not unilaterally terminate a member’s plan, despite a member’ risk profile increasing over time. Member aging, the development of medical science and changes in epidemiological profile all contribute to the rising cost of healthcare, far in excess of a country’s economic growth - regardless of the healthcare system and the country in question. ISAPREs, as key insurance carriers, also make commitments to a healthcare provider who, in turn, have made significant financial investments to deliver timely clinical services and keep medical techniques up-to-date and so respond to their patients’ changing risk profiles.”

Notably, there has been increased public spending on FONASA to account for the rising costs of care among beneficiaries, while ISAPREs have been limited to raising premiums. However, the deficit between what beneficiaries pay and the cost of healthcare is covered by the government. MC2 Salud reports:[25]

It should be noted that ISAPRE plan price adjustments have been less than half of those seen through the budget increases in the State system. Paradoxically, although on many levels FONASA and ISAPREs are competitors, ISAPREs are prohibited from adjusting their prices, whereas FONASA, given the very same rise in productive factor (capital and labor) costs, can ensure any adjustments needed come through its annual budgetary process.”

Nevertheless, despite efficiencies that could perhaps help make ISAPREs operationally viable, the gating issue is the restitution of USD1.4 billion from the system to beneficiaries – which is approximately equivalent to the gross profit of ISAPREs in the last four years (excluding selling, general and administrative expenses and other costs). The balance sheet and cash flows of ISAPREs clearly demonstrate that it would be a challenge for them to make the payments, even if it were over a period of time.

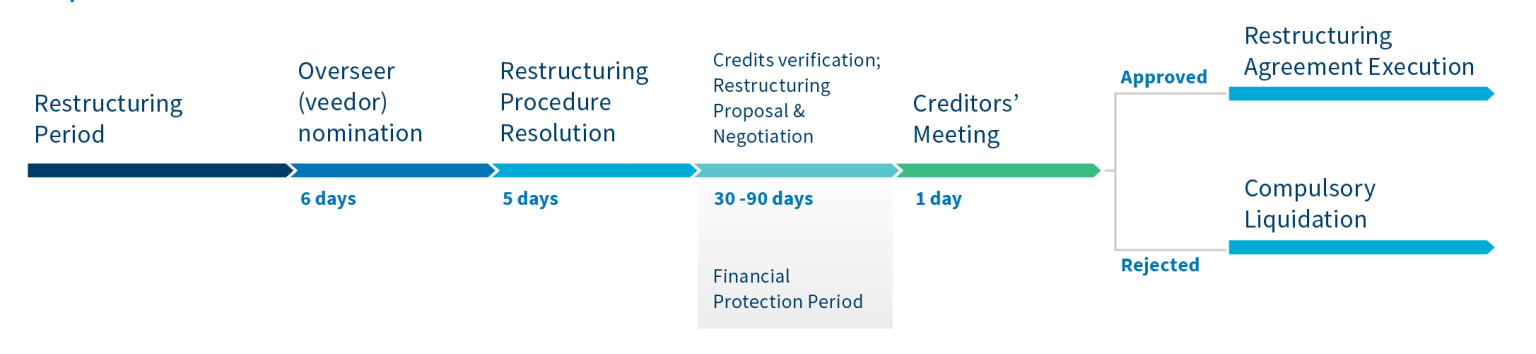

As such, one of the options on the table is a financial restructuring of the debt through a local in-court process or out-of-court restructuring. According to Cleary Gottlieb’s “Latin American Insolvency Regime Scorecard,” Chile unveiled its 2014 insolvency law, Ley de Insolvencia y Reemprendimiento (“LIRE”), to replace its antiquated predecessor in place since 1982. The initial filing, which can only be done by the debtor (company) for its pre-petition debt, provides an automatic stay for up to 30 days, which can be extended for up to an additional 30 days (for a total of 60 days) with two or more creditors representing 30% of liabilities consenting, or up to 60 days (for a total of 90 days) with the consent of two or more creditors representing the majority of liabilities. A plan must then be approved by two-thirds of the creditors present at the meeting, with a required quorum of creditors representing two-thirds of the total liabilities to vote on the plan within each class.[26]

A filing in court for a restructuring may enable ISAPREs to negotiate terms with creditors or a “haircut” to the pre-petition debt owed in order to make them viable. However, a significant obstacle is the 90-day constraint to present a plan to be agreed upon by creditors before converting automatically into a liquidation. To avoid liquidation, creditors representing at least two-thirds of liabilities must agree to allow the debtor to submit a new proposal.[27] A liquidation would not be in anyone’s interest as it would leave beneficiaries without healthcare and any recovery would take years to be paid – and ultimately would not resolve the issue on either side. Another challenge is the fact that ISAPREs are complex entities with many creditors, including their 3 million beneficiaries owed USD1.4 billion (impacting 725,000 contracts).[28] Organizing such a large, diverse group and having a plan approved by thousands of creditors in a 90-day period would be monumental task.

Out-of-court restructurings are more typical in Latin America. In the simplest terms, these seek to bring all the stakeholders (creditors, shareholders and the company) to a consensual resolution in right-sizing the debt and scheduling debt repayments that are satisfactory to both sides, thereby allowing the company room to recuperate and turn around its operations. Often, concessions and/or new money are brought in by shareholders and/or creditors who generally have a vested interest in seeing the company survive and stabilize. However, uncertainty around further actions from the government and/or the Supreme Court make it a more challenging process. In addition, as noted earlier, the majority of the creditors in this case are unique (numerous private individuals), presenting a similar challenge as an in-court solution. Still, with an out-of-court restructuring, there is more time to come to a consensual deal between the parties without the threat of mandatory liquidation.

Currently, Chile’s energy industry is facing structural problems leading to various out-of-court restructurings between companies, shareholders, and lenders. The structural problems stem from the increase in renewable energy supply away from demand centers, transmission constraints from north to south, awarded lower priced power purchase agreements (PPAs) since 2014, historic reductions in precipitation and runoff and high commodity prices. In a perfect storm, Chile’s multi-nodal energy network has resulted in marginal electricity costs to become decoupled in different regions of the country – unfavorable price mismatches at injection and withdrawal nodes – resulting in significant losses to many of the country’s electricity generators.

Over the past 10 years, the Chilean Government has approved a significant increase in renewable solar and wind supply to come online, but has not developed the transmission lines in time necessary to ensure the supply of electricity can reach the regions where demand is prominent – namely the metropolitan region of Santiago. In addition, other existing major transmission lines have had to shut down for maintenance, intensifying network congestion issues. In northern regions where renewables are prominent, geographical power oversupply and transmission constraints have resulted in curtailments (electricity produced that is wasted due to lack of transmission capacity, among other reasons) and near-zero marginal electricity costs during daytime hours. Conversely, in regions where thermal generation is prominent and sets the marginal cost, network congestion issues result in exorbitantly high marginal electricity costs due to the inability to bring cheap renewable energy from other regions of the country.

Making matters worse, exogenous factors are adding fuel to the fire. Chile has faced a significant drought over the past several years which has increased electricity marginal costs in the center and south regions, where renewables are less prominent. Hydro power provides a baseline level of relatively cheap power which has been forced out of the supply mix due to the lack of water resulting in expensive thermal generation to replace it. In addition, the recent increase in commodity prices (coal, oil, natural gas) has resulted in even higher marginal electricity costs (as high as USD300/MWh in certain regions) given the higher share of thermal generation.

The situation is even worse for those companies that entered power purchase agreements (“PPAs”) in the last several years, which likely locked in long term prices in at USD40-60/MWh with distribution companies. When servicing a PPA, generators sell the energy they produce at the market price of the node nearest to them and must buy the energy at the node where their PPA customer withdraws it. The PPA customer then pays the generator the PPA contractual price. Depending on the location of each generator’s plants and their customer, the margin to deliver a unit of power to the distribution companies can be significantly negative to the generator and this is exactly what is occurring to many players in the market.

Earlier this year, several generators formally petitioned the Chilean government to provide a short-term solution to the nodal price differential problem. The government is likely looking into a short-term fix, however, the long-term solution remains the expansion of transmission capacity throughout the entire system. There are currently nine transmission projects and upgrades under construction, which would add 15 GW to the grid between 2023 to 2030.[29] The northern and central regions (where demand is located) will concentrate 11.3 GW (75%) of the additional transmission capacity, while the South, 3.4 GW (25%). The Kimal Lo Aguirre High Voltage Direct Current transmission line, which is currently under construction, will add 3 GW between the north and central nodes with completion expected at the end of 2030. This is a far cry from a short- or medium-term solution, but a necessary project to help ease congestion issues in the long-term.

Challenge: Arbitration

ISAPREs have already signaled willingness to have this dispute adjudicated, rather than to attempt to persuade the Chilean government to reconsider its sweeping regulatory changes or simply adapt via restructuring.

For example, in March and December 2022, the British United Provident Association (“BUPA”) and Banmedica (a unit of U.S. insurer UnitedHealth), sent informal letters of warning to the Chilean government, stating that their institutions would, if necessary, seek compensation under the free trade agreements governing relations between their respective states.[30]

This course of action would require a robust demonstration of the legal merits of the case and ultimately results in a transfer of significant decision-making power to an arbitral panel, with uncertain outcomes.[31]

Arbitration also will require a quantification of the direct financial losses sustained by ISAPREs and would likely include consideration of both the past loss of profits stemming from the standardization of insurance premiums and, critically, any future expected losses.

The arguably more complex task for ISAPREs, however, may be assessing the stakeholder and reputational risk to their businesses in Chile and elsewhere. Some investors may be reluctant to initiate a dispute against the state, particularly if they plan to continue their presence in that state or region in some capacity, as many operate medical clinics and other areas of the vertical chain, as well as provide other insurance products outside of healthcare.

It is important to note that, in many cases, the decision to move to arbitration is not mutually exclusive (i.e., investors may choose to adapt to the dynamic environment through restructuring and/or stakeholder education, while also still demanding to be compensated).

About the Authors

Ana Heeren is a Senior Managing Director and the Head of Latin America for the Strategic Communications segment at FTI Consulting. She brings deep experience and a global perspective to her practice, having developed comprehensive communication plans, public relations strategies, issues and reputation management, and stakeholder engagements throughout Latin America, Europe and the United States. She was named to M&A Advisor’s Annual Emerging Leaders and Consulting magazine’s Rising Stars of the Profession lists in recognition for her work and creation of a multidisciplinary Latin America and Caribbean offering focused on the cross-border communications needs of corporates operating across the Americas.

Ana Heeren is a Senior Managing Director and the Head of Latin America for the Strategic Communications segment at FTI Consulting. She brings deep experience and a global perspective to her practice, having developed comprehensive communication plans, public relations strategies, issues and reputation management, and stakeholder engagements throughout Latin America, Europe and the United States. She was named to M&A Advisor’s Annual Emerging Leaders and Consulting magazine’s Rising Stars of the Profession lists in recognition for her work and creation of a multidisciplinary Latin America and Caribbean offering focused on the cross-border communications needs of corporates operating across the Americas.

Devi Rajani is a Senior Managing Director in the Turnaround & Restructuring practice at FTI Consulting, advising on debt restructurings in Latin America. Devi has more than 15 years of experience working exclusively on large multinational restructuring assignments in Latin America, having restructured more than USD85 billion of debt. Devi brings an unparalleled ability to tackle complex situations given her deep technical expertise, having advised both companies and creditors across a variety of industries, including but not limited to the construction, manufacturing, automotive, hospitality, oil and gas and financial services industries in Mexico, Chile, Brazil and the Caribbean. In 2021, Devi was featured in “Women Driving Change,” a Universal Women’s Network book. She also was recognized at Global M&A Network’s 2021 Americas Rising Star Dealmakers Awards and M&A Advisors’ 11th Annual Emerging Leader Awards.

Tara Singh is a Managing Director at FTI Consulting and leader of the Canadian Valuation & Damages practice. For more than 16 years, Tara has specialized in the assessment of economic damages and the valuation of businesses and other assets, particularly in the context of complex commercial litigation and arbitration including breach of contract matters, intellectual property and securities fraud litigation, class actions, and other financial disputes. She has testified as an expert witness and has prepared numerous expert and valuation reports for submission to Canadian, U.S. and international courts and arbitral panels. Tara was recognized as a Future Leader in the Who’s Who Legal: Arbitration Expert Witness category in 2022.

[1] Asociación de ISAPRES de Chile A.G. “ISAPRES 1981 – 2016: 35 years developing Chile’s private health system,” ISAPRE Trade Union Association 2016, https://www.isapre.cl/PDF/35YEARSIsapres.pdf.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] “Estadísticas por tema,” Superintendencia de Salud de Chile (2023), https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/documentacion/666/w3-propertyvalue-3741.html.

[8] “Coldeco fusiona sus cuatro isapres para estandarizar el plan de salud de sus trabajadores,” CNN Chile (2020), https://www.cnnchile.com/economia/codelco-fusiona-isapres-plan-de-salud_20200215/.

[9] Matthew Malinowski and Eduardo Thomson, “Chile’s private health-care system is on verge of collapse, testing Boric,” BNN Bloomberg (2023), https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/chile-s-private-health-care-system-is-on-verge-of-collapse-testing-boric-1.1893802.

[10] “ISAPRES 1981 – 2016: 35 years developing Chile’s private health system,” Asociación de ISAPRES de Chile A.G. (ISAPRE Trade Union Association 2016), https://www.isapre.cl/PDF/35YEARSIsapres.pdf.

[11] Id.

[12] “Estadísticas por tema,” Superintendencia de Salud de Chile (2023), https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/documentacion/666/w3-propertyvalue-3741.html.

[13] Franco Lopez, “Isapres informaron pérdidas a marzo por $2,152 millones en la previa de la presentación de ley corta,” BioBioChile (2023), https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/economia/negocios-y-empresas/2023/05/09/isapres-informaron-perdidas-a-marzo-por-2-152-millones-en-la-previa-de-la-presentacion-de-ley-corta.shtml.

[14] “Estadísticas por tema,” Superintendencia de Salud de Chile (2023), https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/documentacion/666/w3-propertyvalue-3741.html.

[15] “Chilean supreme court says Isapres can’t raise insurance premiums”, Bnamericas (January 2013), https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/chilean-supreme-court-says-isapres-cant-raise-insurance-premiums.

[16] Matthew Malinowski and Eduardo Thomson, “Chile’s private health-care system is on verge of collapse, testing Boric,” BNN Bloomberg (2023), https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/chile-s-private-health-care-system-is-on-verge-of-collapse-testing-boric-1.1893802.

[17] Eduardo Thompson, “UnitedHealth attacks Chile over new rules that fuel insurance crisis,” Bloomberg (2022), https://www.bloomberglinea.com/english/unitedhealth-attacks-chile-over-new-rules-that-fuel-insurance-crisis/.

[18] Jorge Isla, “Ley corta: Gobierno confirma que las devoluciones de isapres bordean los US$ 1.400 millones,” Diario Financiero (2023), https://www.df.cl/empresas/salud/ley-corta-gobierno-confirma-que-las-devoluciones-de-isapres-bordean-los.

[19] “Encuesta Plaza Pública, Tercera Semana de Enero, Estudio 471,” Cadem Research & Estrategia (2023), https://cadem.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Track-PP-471-Enero-S3-VF.pdf.

[20] Cezary Wiśniewski and Ola Górska, “A need for preventative investment protection?,” Kluwer Arbitration Blog (2015), https://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2015/09/30/a-need-for-preventive-investment-protection/.

[21]Asociación de ISAPRES de Chile A.G., “ISAPRES 1981 – 2016: 35 years developing Chile’s private health system,” ISAPRE Trade Union Association (2016), https://www.isapre.cl/PDF/35YEARSIsapres.pdf.

[22] “Chilean supreme court says Isapres can’t raise insurance premiums”, Bnamericas (2013), https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/chilean-supreme-court-says-isapres-cant-raise-insurance-premiums.

[23] MC2 Salud Healthcare Advisors, “Analysis of the Chilean healthcare (ISAPRE) sector in 2019,” MC2 Salud (2020), http://mc2salud.cl/estudios/MC2%20Salud%20-%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Chilean%20Healthcare%20(ISAPRE)%20Sector%20in%202019%20(07-Apr-2020).pdf.

[24] “Estadísticas por tema,” Superintendencia de Salud de Chile (2023), https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/documentacion/666/w3-propertyvalue-3741.html.

[25] MC2 Salud Healthcare Advisors, “Analysis of the Chilean healthcare (ISAPRE) sector in 2019,” MC2 Salud (2020), http://mc2salud.cl/estudios/MC2%20Salud%20-%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Chilean%20Healthcare%20(ISAPRE)%20Sector%20in%202019%20(07-Apr-2020).pdf.

[26] “Latin America insolvency regime scorecard,” Cleary Gottlieb (2020), https://www.clearygottlieb.com/-/media/files/emrj-materials/latin-america-insolvency-regime-scorecard-february-2020-update.pdf.

[27] Cristóbal Eyzaguirre B, Rodrigo Ochagavía R-T and Santiago Bravo S, “Chile,” Global Restructuring Review (2020), https://globalrestructuringreview.com/review/restructuring-review-of-the-americas/2021/article/chile.

[28] Jorge Isla, “Ley corta: Gobierno confirma que las devoluciones de isapres bordean los US$ 1.400 millones,” Diario Financiero (2023), https://www.df.cl/empresas/salud/ley-corta-gobierno-confirma-que-las-devoluciones-de-isapres-bordean-los.

[29] “Seguimiento de obras en ejecución decretadas y autorizadas,” Coordinador Eléctrico Nacional (2023). https://seguimientoejecucionobras.coordinador.cl/.

[30] Eduardo Thompson, “UnitedHealth attacks Chile over new rules that fuel insurance crisis,” Bloomberg (2022), https://www.bloomberglinea.com/english/unitedhealth-attacks-chile-over-new-rules-that-fuel-insurance-crisis/.

[31] For example, in 2013, the government of Slovakia proposed draft legislative reform which envisaged the creation of a single, state-run healthcare insurer, which would effectively squeeze out private health insurance providers including Achmea, a Dutch-based health insurer. Achmea filed a BIT claim, requesting – among other things – “to order the Slovak Republic to refrain from expropriating Achmea’s investment (Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of 20 May 2014, para. 96)”. The Tribunal found that Achmea had not demonstrated it had a prima facie case on the merits and, consequently, denied its jurisdiction, concluding that “it is not empowered to intervene in the democratic process of a sovereign State (Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of 20 May 2014, para. 251).”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

©2023 FTI Consulting, Inc. All rights reserved. www.fticonsulting.com