2022 Brazil Presidential Elections – A Look Behind the Results

For Parts 1 and 2 of this series, we partnered with Cortex, an external data intelligence company, and used their digital insights to visualize how social media engagement differs depending on user’s political affiliation, and understand how polarization within the Brazilian electoral population has influenced political campaigns and election results.

Expand each section below for a preview.

In a context of high-stakes institutional clashes, massive dissemination of fake news, and stark political polarization, Brazilians are due to vote in the first round of the Presidential Elections on October 2nd, in what many have said will be one of the most consequential elections for the country and the region in recent history. Although there are twelve official candidates for the presidency, polls have indicated for months that there are only two contenders with any realistic chance of either winning in the first round or moving on to the second round of voting that might take place on October 31st: former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the left-wing Workers Party (PT) and the incumbent candidate Jair Bolsonaro, nominated by the right-wing Liberal Party (PL).

For international observers, as well as local academics and journalists, Brazil is buying into the global trend and living in a state of deep political polarization, a term defined as “a state in which the opinions, beliefs, or interests of a group or society no longer range along a continuum but become concentrated at opposing extremes”. In fact, many Brazilians might agree that they do not need experts to tell them what they already perceive: Bolsonaro and Lula stand on opposite ends of the ideological spectrum and have forged narratives that set the other not only as an opponent, but as an enemy that must be defeated for the sake of the nation’s future.

In securing somewhere between 30% and 40% of Brazilian voters (a rough estimate made taking into consideration recent fluctuations and margins of error), both Lula and Bolsonaro have managed to create a deep schism within Brazilian society which cannot be explained solely by virtue of geographic location, social class or religious affinity. The topic of the elections has infiltrated even the most commonplace conversations, generating heated family debates, creating rifts between social groups and even serving as pretext to conduct violent acts. In fact, according to Scott Mainwaring, a LatAm expert, what we are seeing in Brazil is a mixture of polarization and personal hatred: while some voters have chosen a candidate based on ideological affinity, others have identified an enemy and have decided to vote on their opponent, not because they agree with their proposals, but because their victory would mean the other’s defeat.

Polarization is not a new phenomenon in Brazil – in fact, researches pinpoint its origin to the 2013 national protests that sparked from a rise in public transportation fares and ended up encompassing other subjacent issues. Soon after, as immense corruption scandals were unveiled, discontent over the established political class grew, and anger seemed to be directed specifically towards the ruling Workers Party (PT). Dilma Rousseff’s second term, which started in 2014, was overshadowed by the pro-PT/anti-PT dichotomy in Congress and less than two years later, she was impeached. During the same time, a massive corruption scandal erupted in relation to the misappropriation of money from giant state-controlled oil company Petrobras. Former President Lula was portrayed as the mastermind behind the scheme and was sentenced to 12 years in prison for charges of corruption and money laundering.

It was during this difficult time that Jair Messias Bolsonaro appeared in the national political scene, transforming the pro- PT/anti-PT dichotomy into a deeper one of establishment versus anti-establishment. In positioning himself as an outsider ready to combat a corrupt political establishment, Bolsonaro won the presidency in 2018 and continued to govern based on the foundational myth of “us versus them”. This idea pervaded almost every aspect of his tenure, and gave way to other dichotomies, such as the idea that the COVID-19 pandemic could only be managed by choosing between mutually exclusive priorities: public health or economic health.

In March 2021, the Brazilian Supreme Court determined that former president Lula’s trial had embodied a procedural error and annulled his conviction. After spending 580 days in prison, Lula made his way back to public life and declared his intention to run for the 2022 presidential elections, stating that he had been victim of political persecution and refusing to admit any previous wrongdoing.

From that point onward, the 2022 campaign unofficially began, and since then, both Lula and Bolsonaro have unquestionably led voter intentions, with the other candidates consistently lagging behind in polls by more than 20 points (none of them have been able to break the one-digit ceiling in any official poll).

Bolsonaro continues to perpetuate an “us versus them” dichotomy, placing himself as a protective barrier between his followers and the traditional and corrupt political establishment, as well as the idea of socialism (particularly the Latin-American variant, which calls the need to constantly use the economic failures of neighboring Venezuela and Argentina as warning signs). Lula has also approached the debates through dichotomies of his own, mainly that in which people must choose between authoritarianism (on Bolsonaro’s part) and the continuity of democratic institutions (with himself as President).

After months of high-stakes institutional clashes, massive dissemination of fake news, and stark political polarization, Brazilians went to the voting polls last Sunday, October 2nd and voted for President, state governors, some senators, and all federal deputies, state deputies, and federal district deputies.

![]()

Presidential Elections

- Polls constantly indicated that there were only two contenders with any realistic chance of winning: former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the left-wing Workers Party (PT) and the incumbent candidate Jair Bolsonaro, of the right-wing Liberal Party (PL).

- In the days leading up to the election, some polls suggested Lula could obtain more than 50% of the valid votes (winning the presidency in the first round). However, he fell short of that number, amassing 48.43% of the valid votes.

- The biggest surprise was that President Bolsonaro, who polls indicated only had about 35% of voter intention, actually got 43.2% of the valid votes. The 8-point discrepancy in the results has led to widespread critiques of pollsters and the realization that support for Bolsonaro was

largely underestimated. - Both Lula and Bolsonaro concentrated 91,6% of the valid votes – the highest concentration of votes by any two frontrunners since 1989.

- There was a 20.9% abstention rate, the highest of which were seen in rural areas and within the poorest voters. This number is very high, considering that voting is mandatory in Brazil.

![]()

Federal Legislature and State Governors and Legislature Elections

- 12 out of the 26 states are headed for runoff elections for governors. Both presidential

candidates seem tied in terms of alliances with those elected in the first round. - In Brazil’s Federal Congress, the alliance of political parties at the center of the political spectrum, called the “Centrão” (the big center), remains the most powerful caucus. Whoever wins the presidency will have to make concessions and negotiate with them in order to get bills and reforms passed.

- Bolsonaro’s party (PL) grew from 76 to 99 seats in the Federal Congress’ lower chamber, becoming the second largest caucus. In the Senate, the party went from 9 to 14 seats.

- Lula’s party (PT) also grew in both chambers, although with more timid numbers – from 56 to 68 seats.

- This indicates a continued consolidation of a conservative shift that began in 2018 due to anti-PT sentiment, and a slight governability advantage for Bolsonaro if he were to win. However, Congress is bound to remain as polarized as the presidential results themselves.

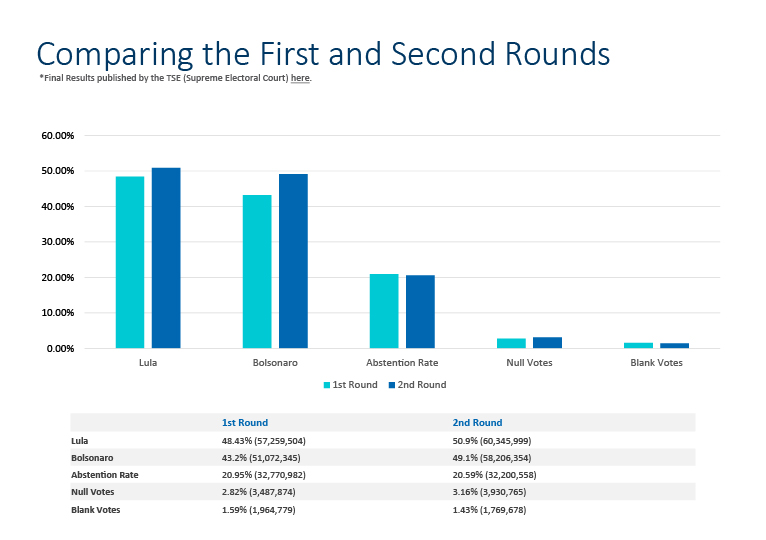

- On Sunday, October 30th, after the fastest vote count in the country’s history, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was declared the winner of the presidential election after obtaining 9% of the valid votes (60.345.999) – Bolsonaro obtained 49.1% (58.206.354).

- The difference between both candidates became narrower in the second round; while in the first round Lula obtained an advantage over his opponent of about 2 million votes, in the second round, difference fell to over 2.1 million votes.

- In the second round, Lula gained over 3 million new votes, mainly in the Southeastern region of Brazil, while Bolsonaro gained over 7 million new votes – a feat that should not be overlooked.

- In a historic shift, the abstention rates were lower during the second round of voting (going from 95% to 20.59% which represented 570,424 thousand new voters).

- This time around, polls predicted voter intention for both candidates reasonably close to the estimated 2% margin of error – 2 days before the election, all of them pointed towards a close race with a Lula victory.

- Notably, during this electoral process, labor law control entities registered a record number of indictments against 1,945 companies that allegedly incurred in electoral harassment by coercing their employees in some form to vote for a certain candidate.

- On that same day, there were also runoff elections for state governors in 12 states. All 26 states and the federal district will be led by governors affiliated to 11 different political parties, out of which only 11 are sympathetic to Lula.

- Governors elected on the first round that declared support for Bolsonaro, specifically in key states such as Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, were not able to change their state’s electoral preference, making the geographic distribution of votes for president by states very similar to that of the first round.

Our publications are in English and Portuguese version can be made available upon request.

How to Navigate This New Scenario?

Schedule a meeting with our team.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

©2022 FTI Consulting, Inc. All rights reserved. www.fticonsulting.com