Show Me The Money

As coronavirus continues to spread throughout the world, the economic contagion is advancing as fast as the disease itself and many governments are witnessing the prompt arrival of a global recession. The Spanish Government will allocate up to EUR 200.000 million to mitigate the social and economic impact of the virus. Where do the funds come from? How will they be distributed? Will they be enough?

There is a broad consensus among experts that this pandemic will have a bigger impact than the Great Recession, but a shorter duration. In this context, many companies are wondering what lies behind the headlines of this aid package and which is the best way to get a slice of the cake. But for the Spanish government is a challenge; on one hand they need to set up a useful mechanism to access the relief package and, on the other hand, they need to maintain the sustainability of its financials and deficit. Primarily, the government’s aim is to limit the duration of the economic downturn to the health alarm and to recover production and consumption levels as early as possible, but are the measures taken suited to this goal?

In a rather late response, Spanish President Pedro Sanchez announced on March 17th the “greatest mobilization of resources in the country’s entire democratic history”. The relief package, based on the Royal Decree 8/2020, of March 17th, on extraordinary urgent measures to address the economic and social impact of COVID-19, will mobilize up to EUR 200.000 million (20% of the Spanish GDP) to combat the effects of Covid-19 in both economy and society.

More precisely, EUR 117.000 million will come entirely from the public sector – of which EUR 17.000 million will be used to assist the most vulnerable – and the remaining EUR 83.000 million will correspond to the mobilization of private resources.

What lies behind the small print of EUR 100.000 million: the so-called “letra pequeña”

In general terms, when a government wants to allocate public resources to a new budget line, income is generated either by raising taxes or by getting into debt. Fortunately, Pedro Sanchez has not applied these measures and has therefore avoided heading Spain into bankruptcy.

Instead, what the government categorizes as public resources or public funding is a credit line worth EUR 100.000 million, managed by the Instituto de Crédito Oficial (ICO) and guaranteed by the State, that will provide credit entities, financial institutions and payment entities with support to give credit to the self-employed, SMEs and large enterprises that request it. It is detailed in Chapter III of the Royal Decree.

The terms and conditions of the ICO guarantee line were approved at the Council of Ministers of March 24th, 2020. The first approved scheme amounts to EUR 20.000 million and was approved on April 6th. The remaining EUR 80.000 million will be activated successively when the first stage is completed almost automatically.

The first EUR 20.000 million will be divided in half, leaving 50% for operations and new loans of up to EUR 1.5 million for the self-employed and SMEs and the other 50% for exceeding amounts to large companies.

Banks are Mr. Wolf

In a nutshell, banks will grant loans that are guaranteed by the State through ICO to the self-employed, SMEs and large companies affected by Covid-19 who need liquidity to face their fixed costs (salaries, invoices and other financial obligations), preventing them from closing down despite a significant drop in their income.

In order to ensure an adequate distribution of the guarantees among all the financial operators (credit institutions, financial credit institutions, payment institutions and electronic money institutions), ICO will divide the amount among them based on their market share at the end of 2019 and will reserve an aggregate quota of 1% to those institutions that did not have a credit balance registered with the Bank of Spain at that time.

Despite the specific requirements to apply for loans, banks may accept or reject requests according to their internal risk criteria.

Therefore, banks assume the risk and distribute the funds provided by the State. In other words, banks are Mr. Wolf. The same way Pulp Fiction pictured Winston Wolf as the fixer, a model of efficiency under pressure and the one who knew how to take care of others’ mistakes. in this Covid-19 scenario, banks fix problems, they make the selection of companies that will access the financing and they are in charge of injecting the money with an adequate flow. It is a smart decision to let banks act as the policeman when opening the door to credit while the government acts as a last resource guarantee.

Eligibility and timing

As we have just seen, it is not that the government has turned the tap on for x million with their eyes closed, but rather it has left it for the banks to take over the credit under a list of conditions.

Banks must convey the advantages of having the State’s guarantee to companies and the self-employed, either by improving the interest rate, offering a longer repayment period or establishing some sort of grace period for the main amount.

The guarantees granted by ICO will cover the main amount of the unpaid loan by the customer, excluding other concepts such as ordinary or late interest. However, loan consolidations and restructurings, as well as the cancellation or early repayment of pre-existing debts, are excluded from the credit lines. By doing this, the government is prioritizing the allocation of economic support to (still) viable situations from others that involve companies that might not be worth saving.

The government is aware that timing is not everything and that banks cannot act alone. In this regard, Spain is urging its siblings (EU member states) and parents (EU institutions) to develop a common plan for the European Union by which countries put money in the companies’ pocket while banks make sure the funds are well distributed. The idea is to create some sort of “mutualized mechanism” that can work as an economic recovery fund, either included in the Pluriannual Financial Framework or another vehicle. However, the coronavirus pandemic is aggravating internal fractures in the European Union, particularly the gap between the north and the south, between creditors and debtors, which was already experienced during the last crisis.

Will this money be enough?

When the Government announced that the first approved scheme of EUR 20.000 million would be activated on Monday April 6th, banks and credit entities warned the executive that this amount wouldn’t even last a day due to the over demand from all eligible categories – large companies, SMEs and self-employed. Indeed, early in the morning, the demand had already exceeded EUR 40.000 million. 80% of requests came from SMEs and self-employed, despite the fact that the total amount was originally divided equally between them and large companies. Banks are now urging the Government to launch the second scheme as soon as possible.

The risk for companies is enormous. According to the latest data from the National Tax Agency (Agencia Tributaria), there were already more than 900.000 companies facing losses in Spain. Emergency financial assistance, on average, accounts for 20% of the International Monetary Fund members’ requests for support.

While an EU mutualized mechanism has been put aside for a while, the Spanish government may hope that this will come sooner than later, in one or other way, and will complement the package already in place.

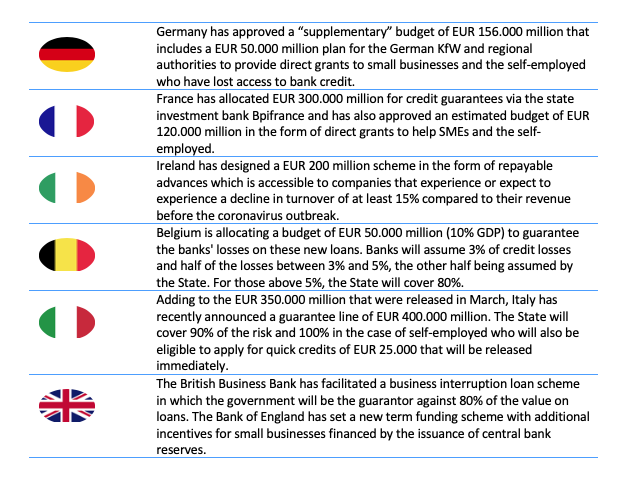

How are other countries supporting companies and business?

So far, most of the measures announced by other European member states have also focused on protecting companies and their employees from the worst of the crisis while supporting healthcare systems. Despite the varying impacts of the pandemic in each of them and the internal political situation, we see a number of similarities in the governments’ response to the virus. Here is an overview of the measures that other central banks and governments are implementing to mitigate the effects of the crisis – cutting interest rates, injecting liquidity in the banking systems and unlocking emergency packages to support specific sectors:

The so called “Social” government: leaving no one behind

The Spanish government has allocated a budget of EUR 17.000 million to support the Extraordinary Social Fund. However, the government’s mindset is to restore the purchasing power of the consumer in order to stimulate demand and consumption, not the injection of steroids through public subsidies itself. Tackling a social emergency when you are a social democrat supported by left-wing partners is challenging and requires unique skills. From an orthodox point of view, some of the social measures introduced by the Royal Decree could be improved but, in the end, a crisis is a game of setting priorities.

Conclusions

Despite the late reaction, the Spanish government has put forward a very consolidated plan to cope with the economic impact of the Covid-19 crisis. Considering the overdemand for loans by companies and the self-employed, it is very likely that the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez will soon activate the second credit scheme, just like other neighbor countries have recently done.

Despite this, some analysts predict a spectacular collapse in the Spanish GDP – even a fall of ~10% in 2020 – the exact economic cost of the crisis is currently uncertain. Spanish IBEX is very volatile, as the last official charts for March show fluctuations of between -5% and +5%.

In Spain, companies are building plans to weather the storm but many of them still don’t know how to act in this unprecedent situation. This is why, in order to contribute to the global effort in fighting COVID-19, companies ought to deploy internal strategies to not only adapt their business models and supply chains, but also to demonstrate advanced crisis preparedness and the ability to unite and engage with other stakeholders from an early stage.

It is crucial for businesses to align their crisis communications and government relation strategies to ensure that the regulatory framework in which they evolve is shaped for the realities of the crisis and its aftermath, since many mechanisms designed by policymakers in times of crisis often become the new standard in the post-crisis environment.