FTI’s Take: The SEC’s Request for Public Input on Climate Change

On March 15th, Allison Herren Lee, the former Acting Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC” or the “Commission”) issued a statement requesting public input on the current status of climate change disclosures.[1] This follows the preliminary recommendation in December of 2020 by the ESG Subcommittee of the SEC Asset Management Advisory Committee that the Commission require the adoption of standards by which corporate issuers disclose material Environmental, Social and Governance (“ESG”) risks.[2]

The request for comment is extensive, encompassing 15 multi-part questions covering a wide range of topics including whether the SEC should require specific ESG or sustainability related certifications for C-suite executives to the granularity with which industry classifications should stratify corporate issuers.

We have reviewed the questions posed by the SEC and have grouped our thoughts – which have been and will continue to be informed by a number of our client relationships with corporate issuers and institutional investors that span every sector of the economy – into three larger themes, including:

- The Commission’s involvement;

- Reporting frameworks & disclosure implementation; and

- Accountability

For reference, the full list of questions posed for consideration by the former Acting SEC Chair Allison Herren Lee can be found on the SEC’s website.

The Commission’s Involvement

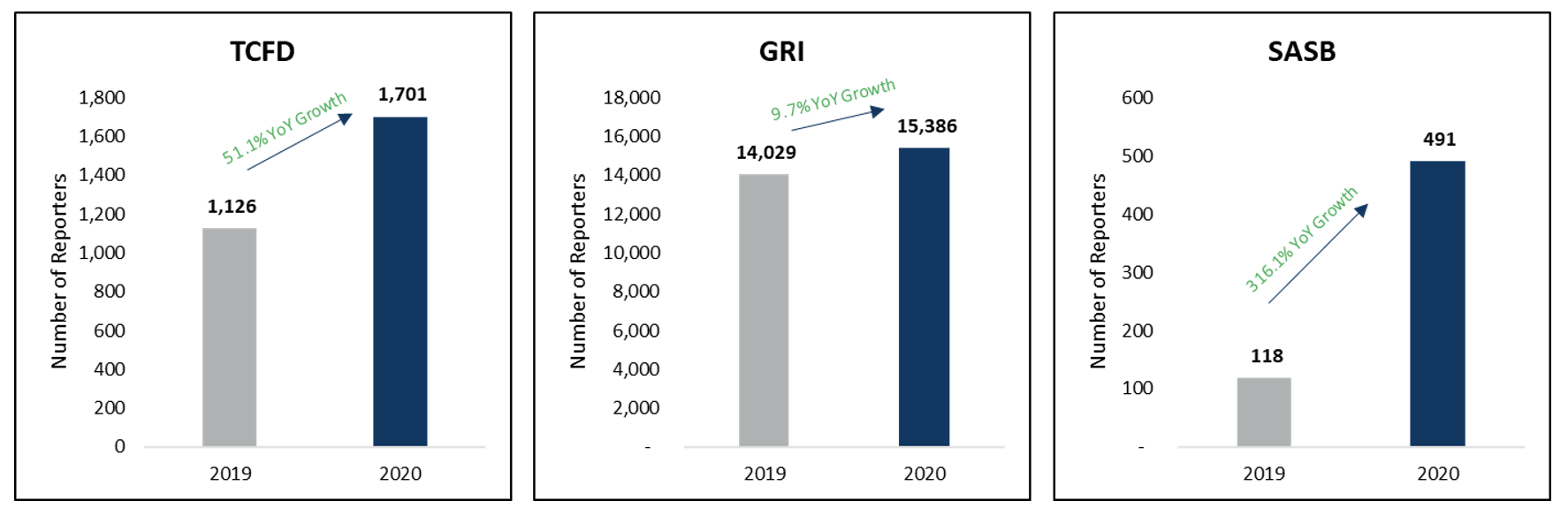

The role of regulation is often to ensure companies act for the benefit of the greater good, and when they do not, to hold them accountable. To this end, corporate issuers have been quick to react to the increased interest in ESG disclosures, particularly from institutional investors, as well as a growing body of empirical evidence that attributes quantifiable value to securities of corporate issuers with relatively superior sustainability disclosures and performance. For context, from 2019 to 2020, adoption of the most widely used ESG reporting frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”), the Global Reporting Initiative (“GRI”), and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (“SASB”) exhibited massive growth in year-over-year adoption among corporate issuers. In fact, reporting under TCFD increased over 50%; GRI gained 1,357 new adopters; and reporting under SASB increased by over 300%.[3]

Further, in light of unprecedented fund flows into sustainability themed investment vehicles, our research and experience dealing directly with corporate issuers and the financial community suggest equity and fixed income markets are largely pricing in climate-related risks and opportunities already. As a result, we are seeing a growing divide between ESG and climate ‘leaders’ compared to ‘laggards’, with the former benefiting from better shareholder returns and valuation multiples. By nature of the market’s efficiency, we would argue corporate issuers are already being held accountable in significant ways for their actions, or lack thereof. Research from various market participants corroborates our view with empirical data.

Per a March 2021 research paper by Dimensional Fund Advisors (“DFA”), Climate Change and Asset Prices, “financial markets process complex information every day…the impact of climate change is no exception.” DFA notes that “overall, a growing body of evidence shows that prices across many different markets (stocks, bonds, climate futures, equity options, and real estate) incorporate information about climate risk.”[4]

Per a March 2021 MSCI ESG Research report, Foundations of Climate Investing, “Carbon-intensive companies have seen a relative downward trend in their price-to-book valuation, which means markets started to effectively ‘discount’ book values that can be linked to carbon-intensive activities. In contrast, companies with high exposure to ‘green’ revenue have seen their price-to-earnings ratios rise, which means investors were willing to pay an increasing premium to gain exposure to technology that has the potential to replace the existing carbon-intensive infrastructure.”[5]

We have also seen a steady increase of institutional investors integrating key ESG factors into their investment decisions. This lines up well with the growing list of signatories of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (“UNPRI”), which promotes the incorporation of ESG factors into investment decisions. UNPRI asset owner signatories grew 21% year-over-year, along with a 17% increase in global assets under management to $23.5 trillion.[6] For reference, global assets under management from UNPRI signatories were less than $10.0 trillion just seven years ago. We are also witnessing the proliferation of ESG rating agencies that have followed suit with in-depth research on corporate issuers as well as the formation of sustainability indices and ESG leaders benchmarks to guide the financial community’s allocation of capital. While just one example, MSCI notes it has developed over 1,500 ESG indices and that approximately $270 billion has been allocated to investments that track or benchmark to MSCI ESG equity and fixed income indices since 2014.[7]

To this end, we would argue that the markets are operating quite efficiently, without any additional regulation.

While climate change may be a pressing issue, we know that corporate issuers are still internalizing the realities of global warming and the associated risks their organizations may encounter. Despite the logistical challenges of voluntary ‘compliance’ with the many well-respected standard-setters, it is the distinct nature of these sustainability reporting frameworks that has facilitated the rapid acceleration in ESG and sustainability reporting among corporate issuers. We are confident that competition and collaboration among the main standard-setters like SASB, GRI, and TCFD is healthy and should continue to enhance the quality and useability of their frameworks for corporate issuers and the financial community alike.

Furthermore, climate change is just one component of ESG. Unless the Commission plans on broadening the working definition of materiality provided by the Supreme Court, we are of the firm and well-reasoned opinion that corporate issuers would still need to leverage additional reporting frameworks like GRI to cater to other stakeholders beyond investors. To be effective, the Commission would need to widen its purview to issues beyond those deemed material under current law, or recognize that their efforts will not solve the problem corporate issuers face today of having to manage detailed inquiries and requests for disclosure from a variety of third parties where the consequences for inaction can be quite meaningful.

In this context, we think it would be most effective for the Commission to endorse or designate standard-setters such as GRI, SASB, and CDP (and by nature of all 3, TCFD’s recommendations), as they all guide the provision of highly relevant and potentially material information. The Commission would likely need to recognize the differences of these frameworks, and where appropriate, embrace the value they bring within and beyond the current legal definition of materiality.

Reporting Frameworks & Disclosure Implementation

The Commission is also seeking comments on the advantages and disadvantages of establishing different climate change disclosure standards for different industries and whether disclosures should be tiered based on the size of the corporate issuer.

Regarding the former, establishing different climate change reporting standards for different industries, is already in practice today through the work of well-respected standard-setters such as SASB. The advantages of industry specific reporting standards greatly outweigh the disadvantages. Per SASB, “different sustainability topics affect different industries in different ways. Even those issues that affect all industries have varying impacts. Although climate change touches nearly every industry in some way, a single metric applied across all industries can’t capture meaningful information about event readiness or disease migration in Health Care Delivery, stranded assets in fossil fuel-based industries, or the energy intensity of data centers in Software & IT Services. Because SASB standards are industry-specific, investors can use them to inform the sector-allocation strategies they use for portfolio construction. Meanwhile, companies can use them to benchmark performance against peers.” To this end, through systematic stakeholder interaction, SASB has developed its own industry classification system – SICSTM – to better account for sustainability risks and opportunities, which do not align perfectly with more traditional industry classification systems such as GICSTM. On this topic, SASB notes, “[SICS] builds on and complements traditional classification systems by grouping issuers into sectors and industries in accordance with a fundamental view of their business model, their resource intensity and sustainability impacts, and their sustainability innovation potential.”

Leveraging existing classification systems that have been designed with direct input from the financial community such as SASB’s SICS industry classification system enables streamlined disclosures for companies that tend to have similar business models, face similar risk and innovation opportunities, operate in the same legal environment, rely on similar resources, and produce comparable products and services.

Not only do industry specific standards aid corporate issuers in assessing their sustainability performance versus peers, they also allow the financial community to evaluate sustainability performance on an ‘apples-to-apples’ basis, similar to how different financial ratios (i.e., P/E, EBITDA margins, etc.) are used to compare companies within a particular industry.

Given the current adoption rates of SASB, we would argue a meaningful overhaul to GICS and SICS classification systems currently depended on by corporate issuers and institutional investors would slow progress and ultimately act as a barrier to further acceleration of decision-useful disclosures. This would be unwise during such a critical moment in time where corporate issuers are beginning to internalize the realities of sustainability and climate change within the context of the various frameworks they have already worked tirelessly to navigate. We recognize there is no ‘ideal’ time to introduce new reporting requirements, but we caution the Commission to consider its objectives of this exercise in light of existing efforts underway, which have already significantly enhanced reporting, transparency, and accountability of corporate disclosures related to ESG and climate change.

With regards to the Commission’s consideration around the tiering or scaling of mandated disclosures based on the size and type of registrant, regulation of this nature would likely have little to no effect on the current ESG reporting landscape. Companies with less resources – often those that are smaller in size – have been and will continue to be at a disadvantage in terms of ESG reporting. For example, in a simplistic scenario, it is much more challenging for a company with a $1 billion market capitalization to compete for investor capital than a $100 billion company on the basis of breadth and quality of the same disclosures. Yet, despite this reality, small-to-mid cap companies continue to invest in ESG program development to elevate the sophistication and decision-useful nature of their sustainability disclosures. We are confident that outsized efforts by small-to-mid-cap companies will not decelerate anytime soon as they continue competing with their large-cap counterparts for global investment capital. If the SEC were to mandate more rigorous reporting for companies above a certain size threshold and/or allow a slower phase-in period on mandates for smaller registrants, we would expect smaller corporate issuers not subject to the same reporting requirements to quickly match the level of rigor and disclosure mandated for larger companies.

We are also of the opinion that size is not necessarily the right variable by which to tier or scale mandated disclosures. For example, we would argue that the financial community desires just as much disclosure, if not more, from smaller companies in energy-intensive industries vs. others that may be larger but operate in industries where resource use is less material.

Accountability

The last of the three themes relates to accountability. In this context, we focus on two key hot-button issues:

- the extent to which the current requirement for certification of financial disclosures by the CEO and CFO should be amended or extended to better account for climate change disclosures; and

- the extent to which ties between employee and executive compensation and climate change are mandated.

Let’s start with a bit of context. Today, CEOs and CFOs of registrants already certify financial disclosures under existing regulation (Sarbanes–Oxley Section 906: Criminal Penalties for CEO/CFO financial statement certification), including those disclosures related to climate change that are deemed material. Regulations such as these have been instrumental in improving accountability and the quality of material financial and non-financial information provided by corporate issuers.

Under existing reporting standards, material factors and risks – including those related to climate change and ESG – should be disclosed in SEC filings. In this context, if change were to ensue on this front, it may be in the form of extending mandated certification beyond the CEO and CFO to that of the ‘Chief Sustainability Officer’, or a role with equivalent responsibility.

As it has with financial disclosures unrelated to climate or sustainability, requiring at a minimum CEO and CFO certification of climate disclosures would in theory enhance accountability by executive leadership when disclosing KPIs they believe accurately represent their climate-related risk and performance. It should also enhance the financial community’s ability to effectively allocate capital. However, in practice, this may also increase the real and perceived exposure of corporate issuers to potential legal liability. As the scrutiny on the quality of climate and ESG disclosures and related accountability intensifies further, we would urge corporate issuers to ensure their data tracking capabilities, processes, and related internal controls are in place organization-wide to avoid risks (e.g., financial restatements) and to improve the quality and predictability of reporting ESG-related KPIs and goals.

The Commission is also seeking input regarding the connection between executive and/or employee compensation and climate change. This, too, is not as straightforward as one might expect. We note that in certain scenarios and within certain industries, climate change risk and impact may be immaterial today and may continue to be immaterial for some time. This reality aligns with the merits of leveraging industry specific standards like those provided by SASB, that highlight how a one-size-fits-all approach to assessing and reporting on materiality does not work in practice.

Aside from the presence or absence of material climate risks and impacts, publicly traded companies are run to optimize profits and shareholder value creation. To this end, broad mandate requiring ties of compensation to climate change would be poorly received by both the financial community and corporate issuers. However, we also recognize this issue will likely not result in any concrete resolution in the near-term. As such, we echo our recommendation to corporate issuers from above; ensure data tracking capabilities, processes, and related internal controls are in place organization-wide so that they are well positioned to effectively compete for global capital regardless of the outcome on the regulatory front.

Conclusion

We have already seen a significant increase in climate related disclosures, particularly from carbon-intensive industries. We would argue this is evidence that the market is operating efficiently and performing exactly as intended – self-regulating both supply – including corporate issuers who disclose climate related impact, exposure, and risk – and demand – including members of the financial community who are requesting said disclosures from corporate issuers. On the whole, these disclosures have been thoughtful, data-driven, and as applicable, provided in accordance with the Supreme Court’s definition of materiality. The market will continue to price in climate-related risks and opportunities where climate ‘leaders’ will be rewarded with lower costs of capital and premium valuations relative to climate ‘laggards’.

While the SEC’s comment period remains open through June, there is little doubt in our minds that this issue will be far from resolved at its conclusion. That said, corporate issuers should not take that as justification for sitting idle, particularly those firms that are in the early stages of their ESG journey.

For the Commission, we offer the following advice: A key pitfall in the ESG reporting landscape today is the absence of SEC-designated standard-setters and a centralized body that clearly highlights the value in each standard setters’ framework. More specifically, it would benefit corporate issuers for a centralized body to indicate how each designated standard can be leveraged to facilitate decision-useful and material disclosures, how they align and/or contradict, and how a registrant in any given industry can leverage these frameworks effectively to enhance the quality and usefulness of their disclosures.

In this context, based on today’s reporting landscape – which we highlight is changing rapidly – we would encourage the Commission to consider the following strategic roadmap to provide greatest benefit to corporate issuers and institutional investors alike:

- Determine which standard-setters are worthy of official designation (presumably, SASB, GRI, TCFD, and CDP);

- Develop a centralized oversight structure with authority to provide guidance to registrants on relevance, applicability, and implementation of designated standard-setters;

- Encourage further collaboration among designated standard-setters to enhance alignment and transparency; and

- Provide clear guidance to registrants on how designated standard-setters specifically overlap with a streamlined roadmap to enable relevant implementation.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.